This article originally appeared as the UCDavis.edu homepage Spotlight on December 17, 2010 but has since been removed from university servers. A condensed version of the text can be found in the Spring 2011 issue (pg. 20) of College Currents, the UC Davis College of Letters and Science Magazine.

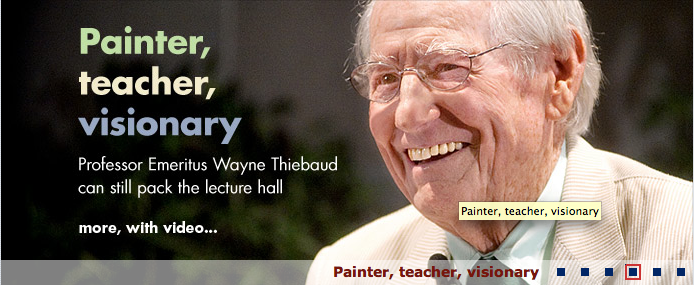

Wayne Thiebaud wears many hats.

He is a painter, a pop art icon, art professor emeritus, avid tennis player, and, as revealed by his recent on-stage conversation with San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker, quite the comedian.

Thiebaud gained prominence for his paintings depicting the mass culture of the 1950s and ’60s, often using sweet treats as subjects.

He formally retired in 1991 after 30 years at UC Davis, then taught one seminar each academic year until the fall of 2008 — bringing to a close his popular course “Art Theory and Criticism.”

So, to no one’s surprise, nearly 300 people lined up inside the Buehler Alumni and Visitors Center in the late afternoon of Nov. 18, awaiting the celebrated painter’s return — as a guest in the Art Studio Lecture Series.

The AGR Room quickly filled to capacity, leaving about 70 people to watch a live video feed in the lobby.

Thiebaud spiritedly reprised his role as professor, commenting on photo slides of paintings (mostly other artists’ works) and discussing them in depth — just as he would have done in his own classroom.

He charmed his audience of students, faculty and longtime admirers with such quips as, “I am goofy, I’m strange. … I’m surreal! I look at the world like this.”

The 90-year-old then proceeded to cross his arms, pucker his lips, squint his eyes and bob his head every which way.

“What a beautiful series of nothingness. What wonderful light!” he mocked.

‘Something visionary’

But Thiebaud, as he would do many times that day, redirected the humor toward more serious matters, often commenting on the place of painting in the world today.

“Painting, in its richest landscape, hopefully offers new insight in terms of what the world might be like, something visionary.”

Such visions may escape us now, he said, but may present themselves to “this group of young painters” — acknowledging the undergraduate and graduate art majors who comprised a majority of his audience — in the future.

Others in the audience included Chancellor Linda P.B. Katehi, who, in her opening remarks, said she immediately agreed to attend the lecture with the intent to learn and be “like one of you, a student.”

Baker, in an interview before the program, said he also has learned a thing or two from Thiebaud.

“To look at art with him is always a great privilege, because he can point out things that you had never noticed before,” the art critic said. “That’s the kind of thing I’m supposed to do!

“He has his hands on the levers, he knows the internal mechanics of painting and its function — in a way that I never will.”

Baker, who met Thiebaud more than 20 years ago, said the artist “stands up for painting in a way that increasingly few people can or do — painting as a way of life.”

Thiebaud does not stop thinking about painting, Baker said, often feeling compelled to return to a particular piece after many years, to deal with “some unresolved issue” or because of “his interest having been reawakened.”

Discovering the real thing

Baker noted that he was not fully aware of Thiebaud’s artistic complexity until seeing his paintings — the real things.

“I knew his work by reproductions when I was living in the East, but there is a kind of energy that they emanate that just can’t be conveyed by reproductions of any kind.

“The work has a very tangible, physical presence, a feeling of the work having been touched. There is also dramatic variation in the subject and size of the work across the years. All of these things were discoveries for me.”

Delectable cakes and cream pies, the subjects of Thiebaud’s most famous works, are seemingly straightforward, but, as the afternoon’s slide show presentation revealed, a painter’s approach to his craft is complicated and deliberate.

In a landscape painting, he observed “the carefully calculated series of relationships” between the background, foreground and middle ground. In a portrait by Van Gogh, he pointed out the sculptural quality of a man’s skull, which he likened to a “wonderful big yellow onion.”

During the lecture, Baker told Thiebaud: “We need people like you because painting is one of the few objects of interest that really requires us to slow down, if we hope to enter into them like the way you were demonstrating.”

With the same patience and careful consideration, Thiebaud built upon the practice of his craft. “Hard work and perseverance,” he echoed again and again, is the secret to his success.

Sit back and ponder

Because of time constraints, Baker showed only two slides of Thiebaud’s work. One of them was Mountain Roads, 2010, recently exhibited in a retrospective entitled “Homecoming” — one of the first shows in the newly expanded Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento.

When Baker asked why the artist chose such a large scale, 3 feet by 4 feet, Thiebaud commented, “In this last series, I have been forcing myself to use as many different sizes and formats as possible.”

After receiving some of the highest accolades of his profession, such as the National Medal of Arts in 1994, Thiebaud still works toward challenging himself with new problems — and new complications.

Wayne Thiebaud is many things but clearly, it is his humility, and his humor, that make him a remarkable teacher.

For the last slide of the presentation, Thiebaud sat back in his chair and said, “I think the best thing now is for me to shut up, and let you hate it, love it, disregard it, be entranced or figure it out.”

In that minute, people in the hall and in the lobby silently examined the abstract forms — loving, hating, disregarding or entranced by it — but actively thinking about the painting, nonetheless.